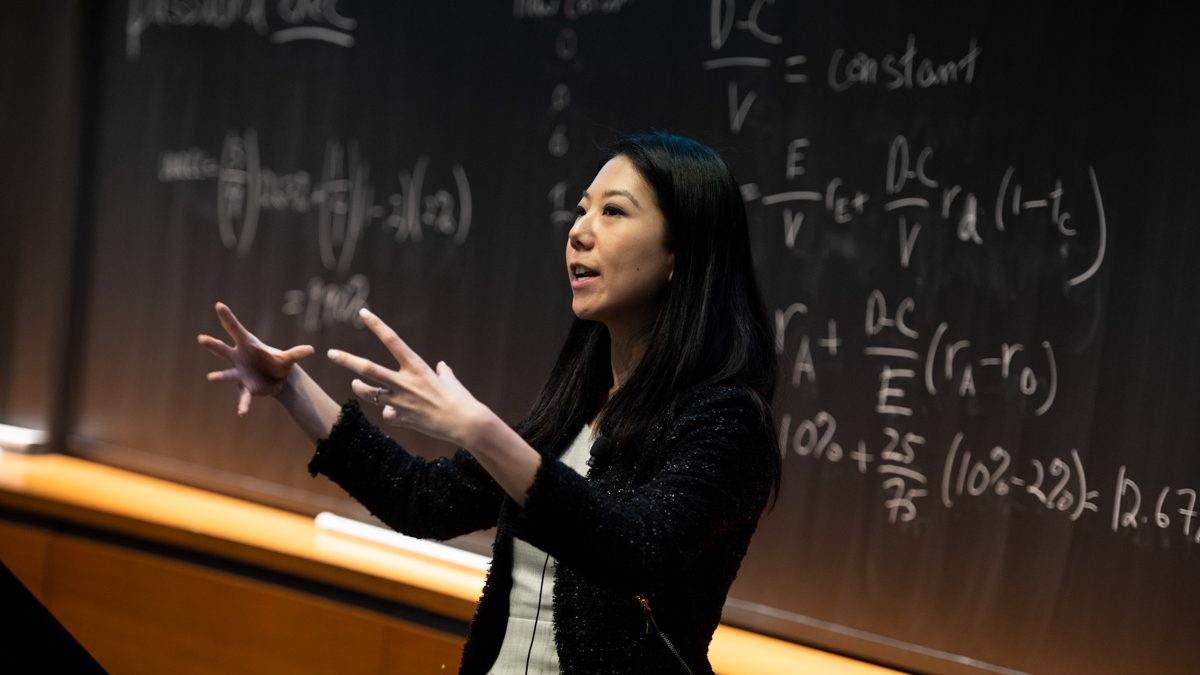

A finance professor at the Yale School of Management specializing in so-called “behavioral economics” and corporate finance says the movement for investors to pull out from high-emitting companies in sectors like energy and agriculture could be counterproductive.

Instead of reducing emissions, this strategy could increase them, and do little to combat the risk of climate change, Kelly Shue said on a recent ARC Energy Ideas podcast.

“Let me be clear that I am very concerned about climate change, and I broadly very much support the ESG and sustainable investing movement,” she said. “What I’m concerned about is the way that it has been implemented by many, but not all, funds to date.

In a study co-authored with Samuel Hartzmark of the Carroll School of Management at Boston College, Shue outlined through data how the “sustainable investing” model rewards companies that by their nature can’t make a meaningful difference in reducing emissions while punishing the companies that could.

The researchers looked at about 3,000 publicly traded companies over the past two decades to examine how their emissions have reacted as their access to financing has either improved or gotten more difficult.

Within each year, the 20 percent of firms with the greatest emissions per unit of revenue were categorized as “brown,” while the 20 percent of firms with the lowest emissions per unit of revenue were categorized as “green.”

“The brown firms tend to come from the energy, manufacturing, transportation and agriculture sectors, [and] the green firms tend to come from services sectors such as insurance, financial services, health care, etcetera,” Shue said.

Sustainable investing strategies would encourage investors to support the “green” firms and divest from the “brown” ones.

But “a 100 percent reduction in the emissions by a green firm is far less economically meaningful than is a similarly sized brown firm reducing its emissions by a mere 1 percent,” noted ARC Energy Research Institute executive director Jackie Forrest.

“Staying invested in a brown firm and asking them to reduce their emissions by 1 percent has a bigger impact to the climate than divesting into the green firms.”

It takes large investments to deliver significant emissions reductions, Shue said.

“Historically, when we look at the data, when high-polluting firms are doing well and getting easy access to public investor money, they’re actually naturally reducing their emissions. They have the financing to buy this expensive green equipment up front that pays off in the future,” she said.

“Meanwhile, if they’re distressed or having difficulty raising money from public investors, they actually increase their emissions, because by cutting back on abatement efforts, that’s actually how they get cash right now.”

In the short term, if investors pull their money from these high-polluting firms, they’re going to become quite distressed and may end up polluting more in their fight to survive, Shue said.

“Right now, they’re investing a lot in abatement efforts and transition technologies and are going to pull back from all of that if we aggressively divest, potentially.”

Many high-polluting industries provide products that are critical to society, she said.

“It’s unavoidable. There’s a number of industries that are high-emitting that produce output that we don’t have ready substitutes for. We need agriculture. We need energy,” Shue said.

“It would be nice to preserve some of the output from these industries and perhaps help them keep on producing output that’s valuable for a well-functioning society, while helping the improving set of firms within these industries.”

She sees hope in “engagement” strategies where investors work with the management of “brown” companies to achieve emissions reduction goals, as well as “transition-oriented portfolios” that direct their capital toward the set of firms within an industry that are improving.

The unaltered reproduction of this content is free of charge with attribution to the Canadian Energy Centre.