Opponents of Canada’s oil and gas industry would like to use the deep but temporary oil demand shock caused by COVID-19 lockdowns around the world as a platform to advance their demands for a “Green New Deal” or “Green Reboot” that would eliminate Canada’s oil and gas industry as soon as possible.

It’s important to consider the accuracy and viability of this movement’s wide-ranging ideas, and what taking on a “Green New Deal” would actually mean for Canadian households.

Oil is ‘a dying commodity’

In a column published this week it was argued that, “The world is starting to move on from oil whether Alberta is ready or not. There is no sales pitch good enough to convince people to invest in the most expensive source of a dying commodity.”

Wrong. While the dramatic current decrease in oil demand is big in the headlines, oil is far from a dying commodity. We are currently experiencing an unprecedented decrease in demand as mobility around the world is curtailed, but recovery is expected to begin in the second half of the year and demand to continue for decades to come.

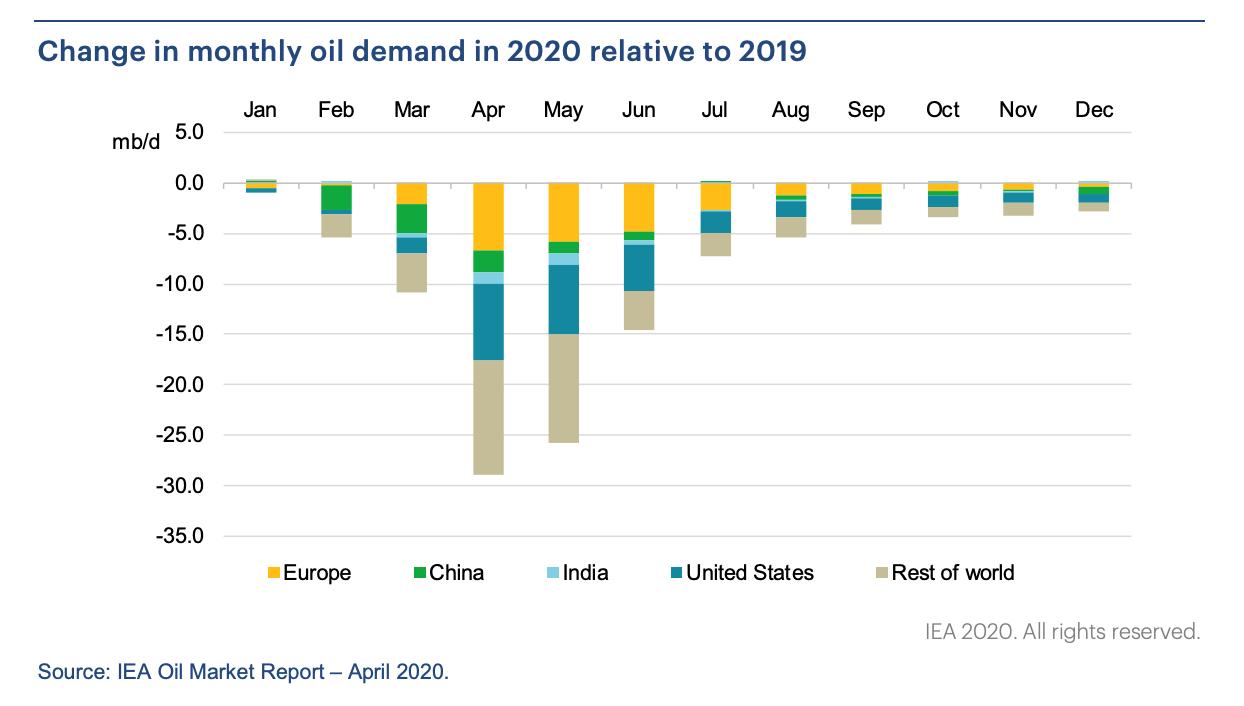

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), in the fourth quarter of 2019, before the novel Coronavirus, global oil demand was approximately 101 million barrels per day. At the expected height of the lockdown response — basically right now — the IEA expects oil demand will drop by a record-breaking 23.1 million barrels per day compared to 2019 levels. But gradually “as economies come out of containment and activity levels rise,” by December 2020 demand is expected to rise back to an estimated 98 million barrels per day – a minimal drop from pre-Covid numbers.

The IEA forecasts that global oil demand will continue to be significant into the future. Even in the most aggressive decarbonization scenario it published in November 2019, by 2040 oil demand is expected to be 67 million barrels per day. But its Stated Policies Scenario, or the more likely case, sees oil demand increase to 106 million barrels per day over the same period.

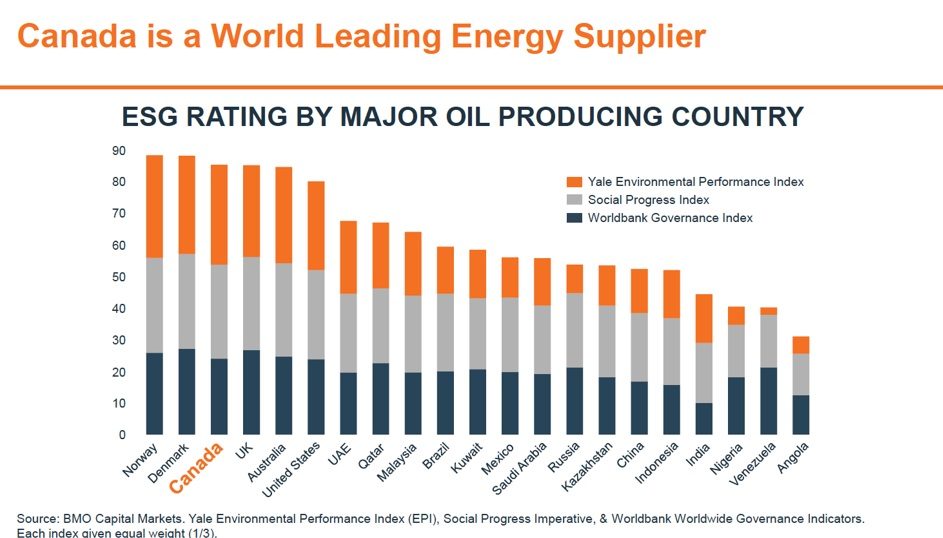

Canadian oil is produced at a far higher standard in terms of environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance compared to oil from other major jurisdictions like Saudi Arabia and Russia that may be less costly to produce.

Arguing to shut down Canadian oil and gas is arguing for it to be replaced by production from jurisdictions that do not take ESG so seriously, while Canadians lose out on the economic benefits of development.

A pact for higher costs

The Pact for a Green New Deal demands that Canada cut emissions in half by 2030. While this includes completely phasing out fossil fuels (see point 3), it actually goes far beyond that in terms of impact to Canadians.

The recommendations include introducing a legally binding climate target for Canada, increasing unionization, increasing subsidies for green initiatives, substantial growth of public investment in renewable energy and infrastructure, and increased carbon taxes.

Cutting GHGs in half by 2030 would require massive carbon taxation. According to Canada’s Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO), Canada’s GHG emissions were 704 megatonnes in 2016. Using 2016 as a conservative baseline, the Green New Deal would require Canada to reduce GHGs to 352 megatonnes by 2030.

Consider that Canada’s Paris agreement reduction target is 513 megatonnes by 2030, and the PBO says that the federal government’s current plan — a $50 per tonne economy-wide tax in place by 2022 — is insufficient to meet that mark. The PBO says achieving the Paris target could require Canadian households to face a $102 per tonne carbon price in 2030. And that’s allowing 161 megatonnes per year more than in this scenario of a Green New Deal.

A 100% renewable economy?

The Green New Deal for Canada includes a goal to fully phase out the fossil fuel industry and move to 100% renewable energy by 2040 at the latest. “We have the ability to build a 100 per cent renewable economy based on public ownership,” the pact says.

No, we don’t. Just this week we were reminded of the inability of renewable resources to completely replace fossil fuels in electrical grids as a subsidiary of Ontario Power Generation (OPG) closed its $2.8-billion acquisition of three natural-gas fired power plants from TC Energy.

“Natural gas is the enabler of renewable energy and provides the flexibility required to ensure a reliable electricity system,” OPG CEO Ken Hartwick said in a statement.

Last May, the City of Medicine Hat, Alberta stopped operating a $13-million publicly-funded solar project, finding after five years that it was not a viable way to reliably replace natural gas for some of the city’s power requirements.

As Michael Shellenberger, president of Environmental Progress, wrote in February 2019, “You can make solar panels cheaper and wind turbines bigger, but you can’t make the sun shine more regularly or the wind blow more reliably…the trouble with renewables isn’t fundamentally technical — it’s natural.”

Distribution of subsidies

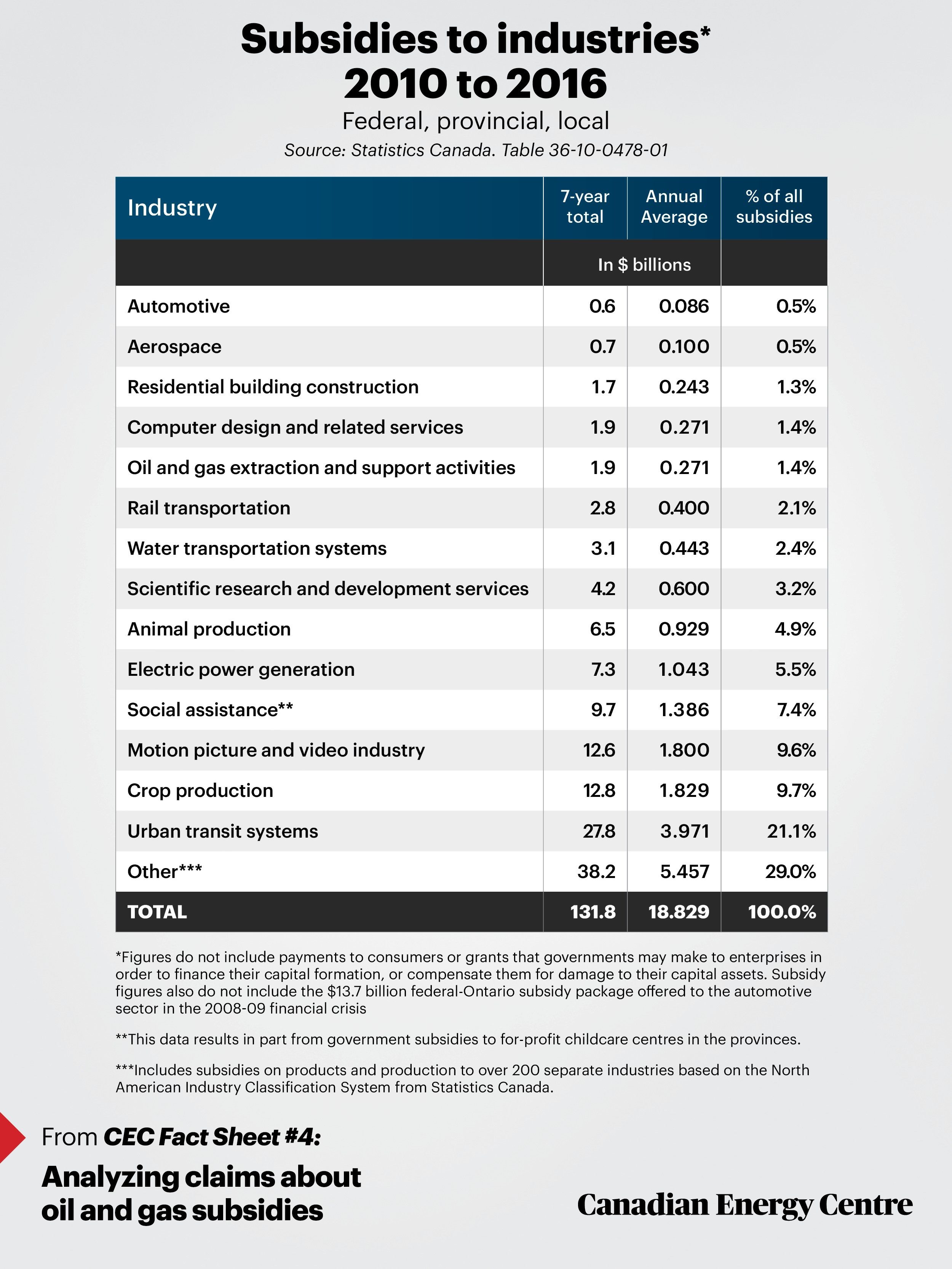

A Green New Deal would demand fossil fuel subsidies from the federal or provincial government to be “immediately eliminated and redirected to support the transition to a clean economy.”

Canadian government subsidies for oil and gas development are already far lower than subsidies for electrical power generation (the bulk of renewable energy activity), according to Canadian Energy Centre (CEC) research.

Using Statistics Canada data, CEC found that federal, provincial and local governments provided $7.3 billion in subsidies to electrical power generation from 2000 to 2017, compared to $1.9 billion for oil and gas extraction.

A 2019 study conducted for the Clean Resource Innovation Network found that Canada’s oil and gas industry spent more on cleantech research and development annually than all other sectors combined — or about 75 per cent of $1.4 billion across industries.

The Bottom Line

The prospect of aid packages and stimulus funding for industries across Canada to recover from the COVID-19 crisis rightly raises questions about how we should be investing in our future. It’s time for a balanced and pragmatic conversation about the best way forward to benefit Canadians. As the country’s largest economic sub-sector, with decades of demand opportunity in the future, this must include oil and gas.

“Some would have us use the current pandemic as an excuse to kick the Canadian energy sector when it is down,” Joseph Doucet, dean of the Alberta School of Business, wrote in April.

“I suggest that we need to ensure that the Canadian energy sector can survive this global crisis and come out with sufficient strength to operate profitably and continue to provide jobs, investments and revenues to governments for many years to come.”