One of the most important but seldom discussed drivers of replacing fossil fuels is the ability or willingness of governments of the 38 members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to do so by further increasing public debt.

Because things have changed materially in the past two years.

First, the pandemic drove government debt to new levels.

Second, the world is experiencing massive increases in costs for electricity and natural gas in multiple markets. Industrial operations are shutting down. Governments are legislating energy price caps and propping up industries. High energy costs and disrupted supply chains are driving up the costs of other necessities including food.

Higher debt makes higher taxes inevitable.

But with rising energy prices and inflation hitting the cost of life’s essentials, who can afford tax increases?

OECD countries are the world’s wealthiest. Until recently, energy shortages were inconceivable. Members include most EU countries plus Canada, the U.S., Mexico, Australia, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Chile, Columbia and Costa Rica.

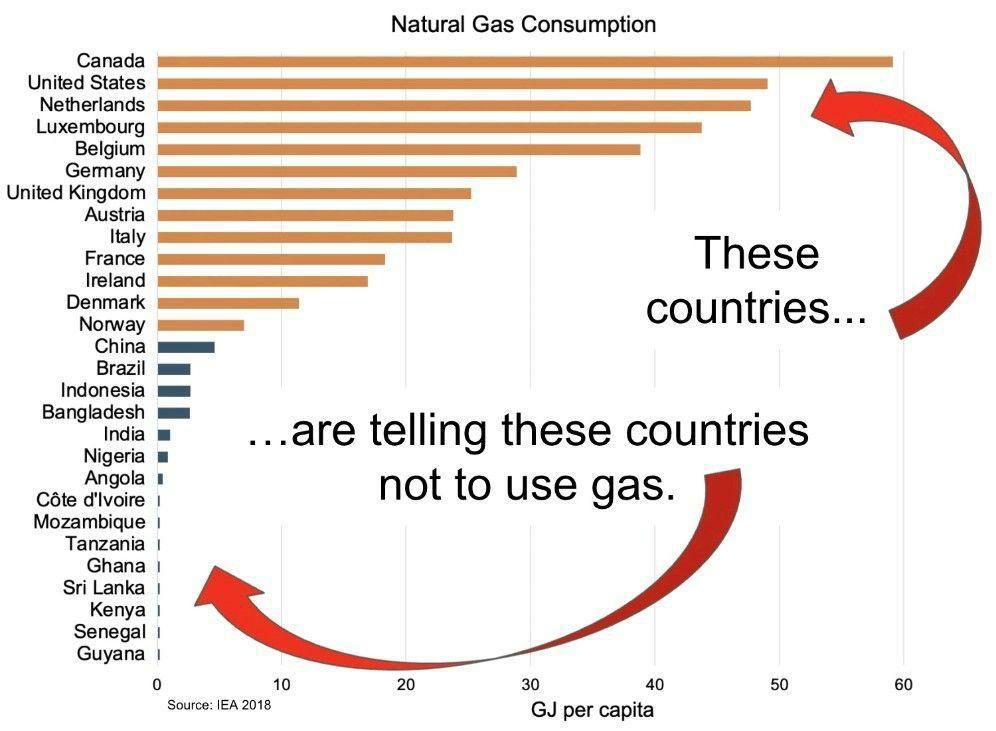

These countries only represent 1.37 billion people or 17.5 per cent of the planet’s 7.8 billion inhabitants. The rest of the world is home to the other 6.43 billion or 82.5 per cent. This includes China, India, Russia, Africa, the Middle East, and Eastern Europe.

OECD countries consume 39 per cent of the world’s primary energy from oil, gas, coal, nuclear, hydro and renewables. On a per capita basis, this is three times the rest of the world.

That OECD countries are energy pigs is well known. Compensation and equalization schemes have been discussed for years. At 2015’s Paris COP 21 climate conference, wealthy countries pledged $100 billion a year for energy transition support by 2020. Six years later this is falling well short.

OECD countries are also leading the charge to replace fossil fuels. “Fighting climate change” has been a proven vote-getter. Many elections have been won in Europe and North America by pledging to do more.

But the commitments get more attention than the cost. And success remains elusive.

The global climate behavior narrative driven by the world’s wealthiest is wearing thin. An organization called the African Energy Chamber is becoming increasingly vocal. Executive chairman NJ Ayuk wrote in a news release, “Make no mistake, we are going to Glasgow (COP26) and will be proudly supporting the African energy sector and demand a just transition.”

He recently posted this image on LinkedIn.

An October 18 Wall Street Journal headline blared, “To Strike a Climate Deal, Poor Nations Say They Need Trillions From Rich Ones.”

Not only have past commitments failed, but the developing world wants much more money to do what they’ve been told they must. WSJ reports that in Glasgow, African nations will be asking for “$1.3 trillion annually by 2030.”

But there are other serious issues besides what is coming at COP26.

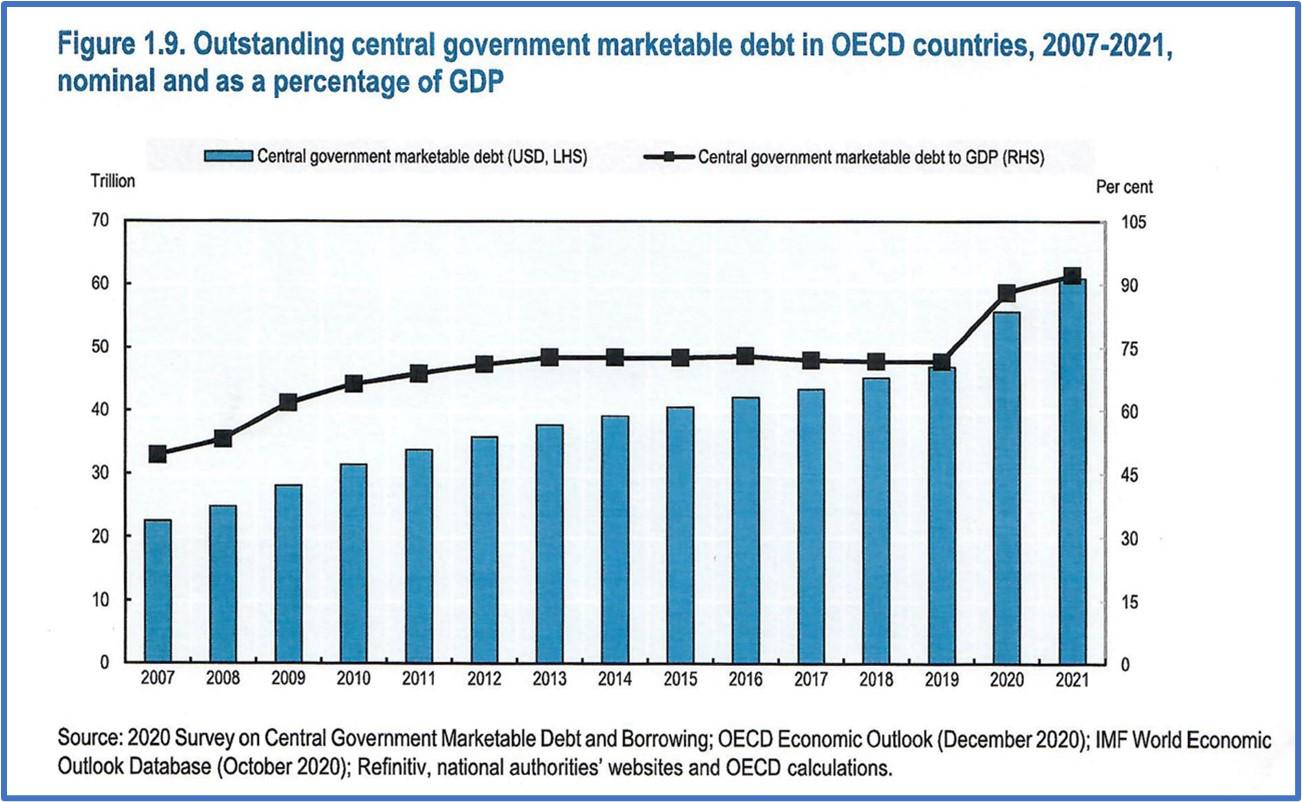

Before the world financial crisis of 2008/09, total debt of OECD members was about US$22 trillion with a debt-to-GDP ratio of 33 per cent. The response by central banks to that crisis was to flood capital markets with liquidity. Coined “quantitative easing,” it worked. Record low interest rates helped significantly.

However, the debt-fueled party never ended. While the economy recovered and appeared to be growing, heavy government debt stimulus disguised true economic performance. Debt increased every year, as did the debt-to-GDP ratio.

The pandemic response caused debt to spike higher yet. By the end of 2021, total OECD debt is expected to be four times what it was in 2007, and the debt-to-GDP average will be over 90 per cent, almost triple 2007 levels.

The ability of taxpayers – individual and corporate – to service these significantly higher debts levels and cope with inflation and rising energy costs is finite.

To control inflation, central banks have historically raised interest rates. But as public and private debt mounts, this will be painful. The combination of higher interest rates and rising costs for life’s necessities will put significant negative pressure on economies struggling to recover.

Then there’s climate change.

This isn’t how the master plan was pitched. A year ago climate action advocates were promoting Build Back Better, Resilient Recovery and the Great Reset. Governments could and should borrow more to lead the energy transition and drive a green recovery.

But with all the other new and powerful external market forces in play, can OECD countries still afford to execute the pre-pandemic climate playbook?

David Yager is an oil service executive, oil and gas writer, energy policy analyst and author of From Miracle to Menace – Alberta, a Carbon Story. More at www.miracletomenace.ca

The unaltered reproduction of this content is free of charge with attribution to Canadian Energy Centre Ltd.