The political success of Alberta premiers dating back 50 years has been closely linked to the oil and gas business and federal/provincial relations.

Premiers fortunate enough to be in office when the oilpatch and economy were booming were popular and won multiple elections. Challenging the federal government when its policies negatively affect Alberta has been a reliable vote-getter, especially when it involves resources.

Those who were in office when Alberta’s main industry was struggling, or were seen as cooperating with Ottawa when its policies negatively affected oil and gas, have not been treated as kindly.

The primary drivers of Alberta’s resource prosperity are geology, market access and world events. The government of the day invariably takes credit when things are good, and gets more blame than it should when they aren’t.

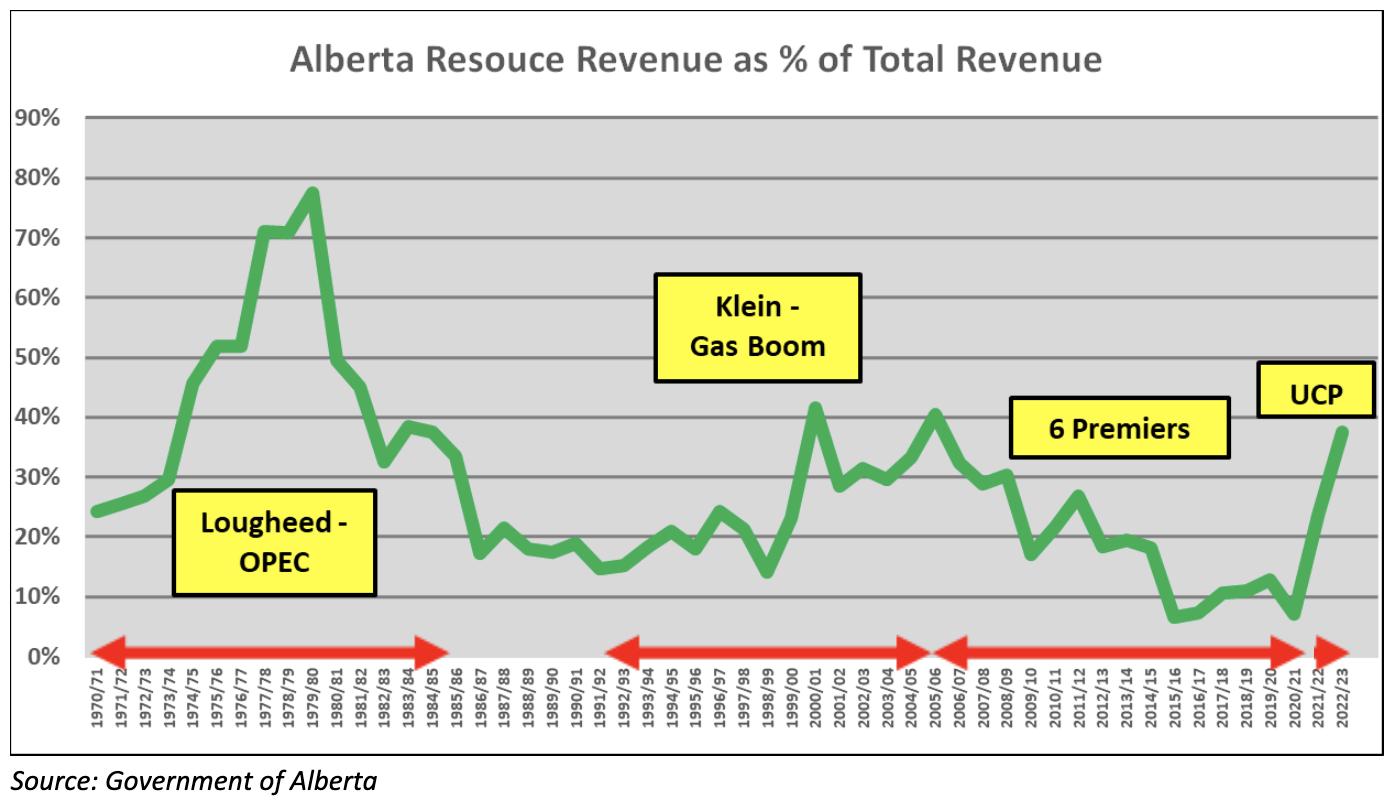

This chart shows the percentage of total provincial funding provided by non-renewable resource revenues back to 1970. The two longest serving premiers governed when oil and gas were very kind to Albertans and the treasury.

Good government, good fortune or both?

In 1971, Peter Lougheed’s Progressive Conservatives replaced the Social Credit dynasty that had governed since 1935. That year the province received nearly 25 per cent of its budgetary revenues from non-renewable resources.

Lougheed’s administration got a huge boost in 1973 thanks to OPEC. Over the next seven years the price of oil increased by a factor of 10, creating an economic boom of previously unimaginable proportions. By 1978 over 77 per cent of the province’s revenue came from resources. New ways to deploy all the cash included creating the Heritage Fund.

But this newfound prosperity also caught Ottawa’s attention, resulting in epic political battles with Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau over provincial resource revenues and control.

These two circumstances made Lougheed fabulously popular. He won four elections before stepping down in 1985.

Federal/provincial tensions were not this strained again until Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was elected in 2015 and picked a different fight with Alberta, this one over production growth, emissions and climate change.

In 1986, Don Getty took charge of a much different Alberta. The oil price collapse, recession and high interest rates of the early 1980s clobbered the province. Getty faced big spending, collapsed revenue, and the belief that direct government investment could successfully diversify the economy.

In 1992 Calgary mayor Ralph Klein won the PC leadership on a platform of cutting spending. By the late 1990s, rising gas prices and production volumes vastly improved provincial revenues. This was followed early this century by higher oil prices and huge oil sands expansion.

As Alberta’s economy recovered, Klein was very popular and won four elections. By 2004 Alberta had retired all its debt, put $17 billion in the Sustainability Fund, and had enough spare cash to send $400 to every Albertan in 2005.

But after Klein got only 55 per cent support at a PC leadership review in 2006, he stepped down as leader. That was the same year that resource revenue exceeded 40 per cent for the first time since 1982.

Over the next 16 years, six premiers – Ed Stelmach, Alison Redford, Dave Hancock, Jim Prentice, Rachel Notley and Jason Kenney – encountered multiple economic challenges on resources, some self-inflicted. After resource revenues peaked at $14.3 billion in 2006, they began declining because of falling natural gas prices and volumes and later oil prices. The five-year average from 2015 to 2021 was only $4.5 billion.

At the same time, government spending increased significantly because of infrastructure required to support continued population growth, much of it related to the oil sands construction boom. Deficits and debt grew quickly.

For Alberta’s treasury, the total cost of oil sands expansion preceded offsetting royalty income by many years.

Then because of climate change, the western world declared war on fossil fuels and Alberta’s oil sands. Pipelines were blocked. Capital fled. Global capital providers virtue-signaled by refusing to continue to finance Alberta oil.

From 1970 to 2015, resources supplied an average of 30.9 per cent of provincial revenue. Because of collapsed commodity prices and rising spending, from 2016 to 2021 it was only 9.2 per cent.

All that changed in 2021. As the pandemic lockdowns ended, oil and gas prices began increasing. Because of geopolitical events, prices soared in early 2022. More oil sands projects finally reached payout and started paying higher royalty rates.

Alberta is back in the chips in ways nobody imagined a year ago. The latest budget update reads, “The 2022-23 first quarter revenue forecast has dramatically changed, with West Texas Intermediate oil prices expected to be US$22 per barrel higher than estimate in Budget 2022, and resource revenue up to $14.6 billion.”

Revising its Budget 2022 estimates, for 2022/23 Alberta now forecasts resource revenue could reach $28.4 billion and provide 37.4 per cent of provincial revenue.

Because of federal policies since 2015 and the continued plan of accelerated emission reductions and rising carbon taxes, the kindest word to describe Alberta’s political relationship with the federal government is “strained.”

It could get worse.

If the province’s financial targets materialize – and if a recession, inflation, rising interest rates and falling house prices again make Alberta’s prosperity conspicuous on the national stage – then what? If Alberta booms while the rest of Canada struggles, how will that affect federal policy?

Petroleum and Alberta politics are intertwined. That’s unlikely to change.

David Yager is an oilfield service executive, oil and gas writer, and energy policy analyst. He is author of From Miracle to Menace – Alberta, A Carbon Story.

The unaltered reproduction of this content is free of charge with attribution to Canadian Energy Centre Ltd.