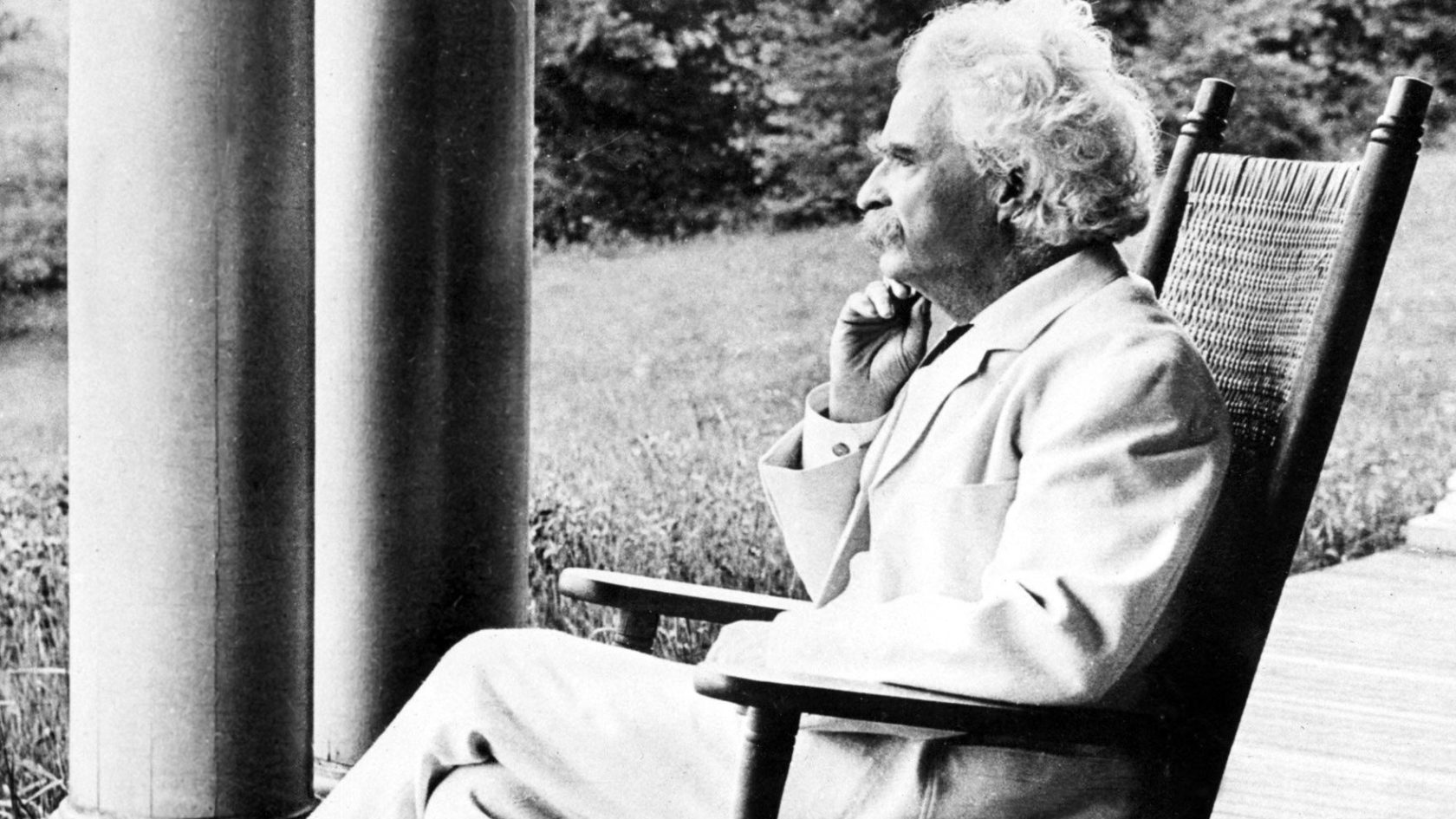

In 1897, while in London in the midst of a worldwide speaking tour, the American author Mark Twain became the subject of rumours back home that he was dead. To get at the truth, a reporter from the New York Journal wrote to Twain to ask if he was indeed dead or gravely ill.

In response, Twain, with his usual wry wit, wrote back chronicling how he’d also heard the rumours of his illness: “I have even heard on good authority that I was dead.” Twain explained that the gossip resulted from his cousin’s illness and mistakenly spread from there. “The report of my illness grew out of his illness. The report of my death was an exaggeration,” wrote Twain.

Something like that mistaken assertion about Twain now faces the oil and natural gas industry worldwide and in Canada: that oil and gas demand will never resume from the steep decline now occurring as a result of coronavirus and the near-worldwide lockdown’s effect on the economy.

Some anti-oil and gas advocates are sure of this, and are demanding that Canada somehow “transition” away from oil and gas. But that’s not possible, according to the informed opinion of University of Manitoba Professor of the Environment (Emeritus) Vaclav Smil.

The barriers to a transition ordered via government policy were summarily addressed by Smil in his 2017 book, Energy Transition: Global and National Perspectives. In it, Prof. Smil pointed out that, “As in the past, the unfolding global energy transitions will last for decades, not years, and modern civilization’s dependence on fossil fuels will not be shed by a sequence of government-dictated goals.”

It’s important to note that Smil wants to see renewables succeed. He is also concerned about carbon emissions and their effect upon global temperatures. But the energy professor prefers to deal in hard facts and actual data that result from understanding the physical properties of various forms of energy, the energy density “punch,” as one journalist characterized the issue.

Back to oil and gas demand. The coronavirus pandemic has severely impacted consumption of both in the short-term. However, in previous recessions, oil consumption declined (though natural gas did not always follow the same pattern) before demand resumed and increased.

For example, since the 1970s temporary declines in oil consumption were followed by a return to ever-higher consumption. In the last recession, daily oil consumption fell from 87.1 million barrels in 2007 to 85.8 million in 2009, a 1.5 per cent decline. After that, consumption then rose by ten times that decline, or 15 per cent, to reach 98.8 million barrels of oil consumed daily in 2017 (the latest year for which comparable annual data is available from the U.S. Energy Information Administration).

On natural gas, until this recession world consumption declined only once since 2000: during the 2008/09 recession, by just over three per cent. After that and by 2017, consumption rose by 25 per cent.

Past trends are not guaranteed to repeat in the future. However, the U.S. Energy Information Administration forecasts that petroleum consumption worldwide will decline by 5.2 million barrels in 2020 from 2019, a 5.2 per cent reduction, before rising again in 2021 by 6.4 million barrels, a 6.7 per cent increase.

That forecast is an annual average, so it looks beyond just the massive double-digit drop in demand that has occurred in recent weeks. It assumes an end to the current economic shutdown and a partial economic recovery later this year and next.

The U.S. agency does not provide a natural gas forecast but before the crisis, the International Energy Agency (IEA) forecast a 40 per cent rise in world natural gas consumption by 2050.

Back to the “Twain” assertion — that oil and gas is dying. Canadians have heard this for a decade, with the same voices predicting and demanding the sector’s demise.

They were incorrect. But the result of the activism and blocked developments (among other factors) meant that while some Canadians were debating if Canadian oil and gas extraction should be “allowed” to survive, American oil and gas producers created 95,000 new oil and gas extraction jobs between 2009 and 2018. In Canada, just 1,610 oil and gas jobs were created in the same period.

In crises, is it hard to think beyond the severe economic destruction immediately underway. But unless the Coronavirus and associated lockdowns continue for decades — not a position advocated by any government, anywhere — the death of oil and gas is greatly exaggerated. The only question is if Canada will play any part in the world’s oil and gas future when demand resumes.