It may be invisible to humans, but methane won’t be able to escape the high-tech eye of Claire, no matter where on Earth it’s being generated.

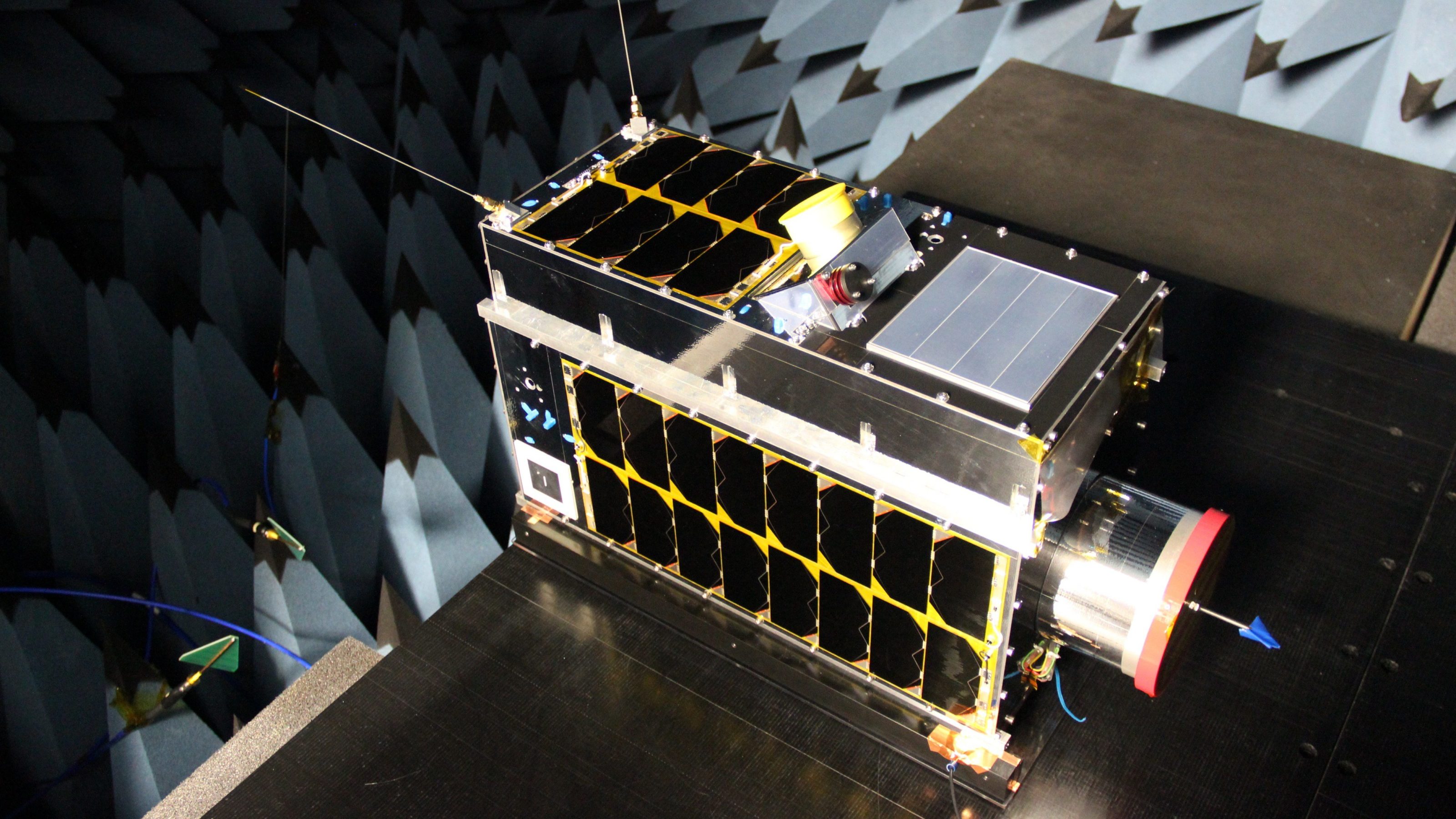

Montreal-based GHGSat Inc. joined world leaders at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland in January to announce it will be using the microwave-sized satellite to create a free map that will visualize global hotspots of methane. The greenhouse gas packs 25 times more global warming potential than carbon dioxide.

Joining forces with the European Space Agency’s Copernicus Sentinel satellites, as well as other orbiters that have similar monitoring technology, the company will formally launch its global methane emissions map at this year’s United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP26, in Glasgow, Scotland in November.

Methane accounts for about one-fifth of the warming the planet has experienced.

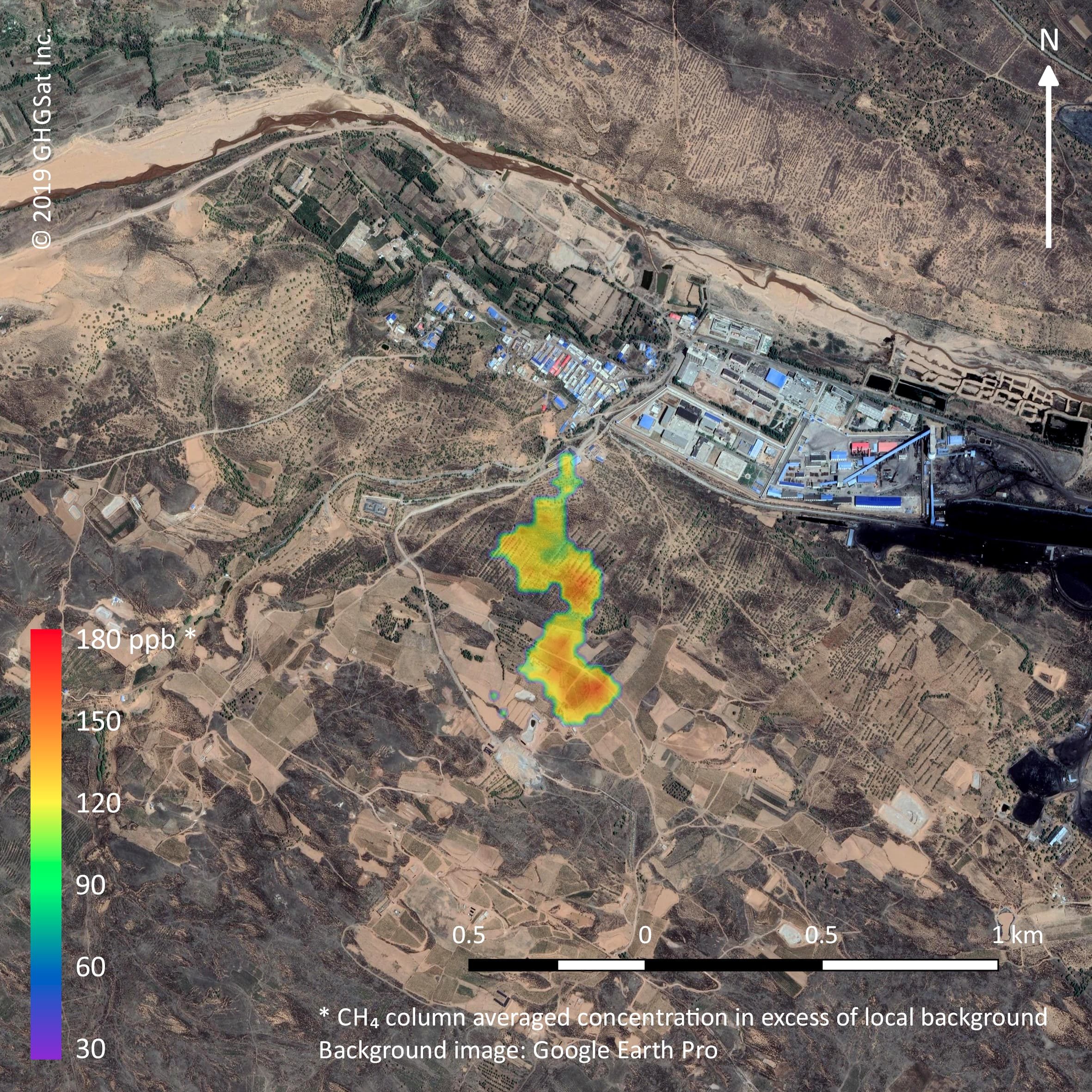

Stephane Germain, president and CEO of GHGSat, said while significant data is currently available for researchers to crunch methane emissions in many parts of the planet, this will be the first time it is presented visually, with a navigable map that will allow users to zoom in to a 2 km x 2 km grid anywhere on land. Higher resolution methane emission measurements, up to 25 m x 25 m, will be available to those who sign up under a paid subscription service.

“This is something that will raise awareness and questions about what can be done to mitigate these emissions,” Germain said.

“I think for the broader community there will be surprises. They might be surprised to see the amount of activity in the Permian Basin or in some parts of China, for example.

“And that may lead to questions about why, and what’s going on?”

Launched in 2016 on India’s Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle, the 15-kilogram spacecraft travels at more than seven kilometres per second while circling the planet about 15 times a day in a polar orbit. Claire, also known as GHGSat-D, first took flight thanks to a collaboration between the company, Canada’s Oil Sands Innovation Alliance and Suncor Energy Inc.

Dozens of clients have since signed on, keen to harness the valuable data generated by Claire.

The environmental value and potential to help combat climate change has already been demonstrated by the unwavering eye in the sky.

In early 2019, Claire unearthed a massive methane leak at the Korpezhe oil and gas field in Western Turkmenistan. After a series of flybys, it was determined that about 142,000 tonnes of methane had been released, prompting the company to work through diplomats to put an eventual cork in the GHG-billowing leak.

Later this year, Germain said he hopes to launch Claire’s cosmic sibling Iris, followed by Hugo sometime in 2021.

“We’re going full speed, pedal to the metal – we’re planning to launch 10 more satellites in the next two years,” he said, adding like the initial trio all will bear the names of children of members of the project’s team.

Down the road, Germain said he would also like to see the detection of CO2 added to network of satellites, noting the platform would allow for that as well.

“At the end of the day, CO2 is the largest volume (of GHGs), but there’s greater insight probably to be gained by measuring methane,” he said.

“If we can let people know that this capability exists today, it drives people to understand the global transparency that’s here now, and help people better understand our emissions.”