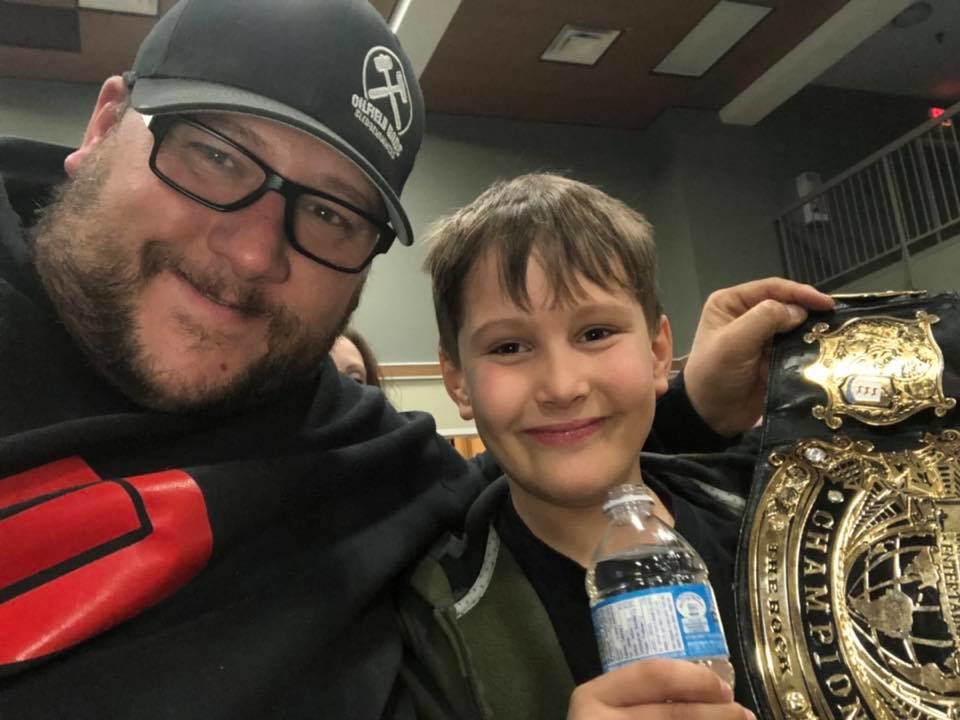

Ottawa’s recent announcement of support for the struggling oil and gas industry during the COVID-19 crisis is disappointing for Chad Miller and Oilfield Dads — the large online community he created.

The 39-year-old Métis pipeline and facilities consultant, who wears many hats such as heavy equipment operator and journeyman pipefitter, lives in Sylvan Lake, Alberta with his wife and three children. He says Ottawa’s commitment of $2.5 billion, partly in repayable loans, for inactive and orphan well clean-up and methane emissions reduction does little for the thousands of people like him who have lost their jobs.

“You’re throwing us a bone, but that’s only going to help around 6,500 people — what about the rest of the people who are sitting at home?” he says. “We’re living on a double-edged sword here with the COVID and the oil price drop.”

Oilfield Dads, which Miller created following the oil price crash in 2015 as a support network for oilfield workers struggling because of being out of work, now has more than 10,500 members.

“We are the rough and tough guys, but we still feel and have families and are real … I’ve had a lot of people share stories with me and write stories to me about how this page has helped them know they are not alone in the struggle, and even helped some of them from committing suicide.”

Oil and gas is Canada’s largest economy sub-sector, directly and indirectly employing 540,617 people in 2016 and paying $359 billion to governments between 2000 to 2018, according to Canadian Energy Centre research.

Before COVID, things were starting to improve for the sector, with major infrastructure projects like the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion and LNG Canada underway to connect supply with consumers. For the first time in five years, in January the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers announced an expected increase in oil sands capital spending.

Now, thanks to a deep but temporary demand shock due to the COVID-19 lockdown around the world, oil prices have dropped into the negatives and the cautious optimism has been erased. Capital spending in the oil sands sector, for example, is now expected to be the lowest in 2020 it has been for more than 15 years, according to IHS Markit.

The crisis-level outlook is temporary. Oil demand is expected to drop by 19 million barrels per day (or almost 20 per cent) during the second quarter but rise back rapidly after COVID measures are lifted this summer, growing to pre-pandemic levels by the third quarter of 2021, according to a new report from Sproule.

Kevin Birn, IHS Markit

“We will get on the other side of this, and when we do it will look different, but oil and gas is going to continue to be an important part of the energy mix on the other side. But for many nations including Canada, recovery won’t be as simple as walking out from our homes. It will likely take time for many people to return to work and for our economy to recover,” says IHS Markit vice-president Kevin Birn.

“For Canada, oil and gas is an important part of its economy and getting the industry back up on its feet as fast as possible is an important part of restarting its economy.”

The light on the eventual horizon does little to help businesses in the near term. The Royal Bank of Canada is forecasting that employment will plummet by 440,000 jobs in Alberta and 80,000 in Saskatchewan during this crisis.

There will be “a huge human toll to get through this period,” Birn says.

“This is more than looking at capital. As analysts, we tend to look at dollars, but this is about people. This is about a hollowing out of the human capital of an industry to the point where companies may be unable to sustain operations.”

The concern for many businesses in the oil and gas industry is the same as it is for other sectors: the ability to keep the lights on until demand comes back “on the other side” of the lockdown.

Ottawa announced last week it expects to maintain 10,000 jobs across Canada by investing $1.7 billion to clean up orphan and inactive wells in Alberta, Saskatchewan and B.C. and creating a $750 million fund to focus on reducing methane emissions from oil and gas. It will also provide loan support for producers under 100,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day through Export Development Canada.

The investment is welcomed but much more is needed, says Canadian Chamber of Commerce CEO Perrin Beatty, who during the pandemic has raised concerns that low prices and insolvency among Canadian oil and gas producers could “jeopardize the resiliency of Canada’s energy system.”

“The demand destruction from COVID-19 has turned the energy sector on its head. For a sector subject to heavy regulations, clarity and commitment from the federal government are crucial in carving a path forward,” Beatty said on Monday.

“We remain hopeful for additional measures from the government, especially those that provide much needed liquidity. There is much more that can be done to ensure Canada’s energy sector is positioned not only to recover, but to be a leader in kick-starting Canada’s economy.”

A lack of support for Canadian oil and gas has national and international implications, according to energy investment icon Mac Van Wielingen.

“Not only are we compromising our own economic, social, and governance standards, looked at from a global perspective, I believe we are also compromising the world’s environmental aspirations,” Van Wielingen said during a keynote speech to the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers’ virtual investment symposium on April 8.

“If our focus is to reduce global emissions, and we can bring on new [oil] supply that has less emissions than the average in a particular market, how do we justify restricting our own volumes? …If we know that our LNG is probably the greenest in the world, and that our LNG would replace high emission intensity coal, how do we justify saying no to our own developers?

“How do we justify giving up the investment activity, the jobs, and the tax base needed to fund our own social needs? How do we justify ceding the market to other suppliers in jurisdictions that have far inferior environmental, social, and governance standards?”

Oilfield dad Miller says he shares the desire for a greener, safer world, and his experience on the ground is that Canada’s oil and gas industry does too.

“We have the highest environmental regulations in the world,” he says, adding that leadership position increases frustration about job losses.

“The oil and gas sector is the heart of Canada, and we drive the economy. It trickles down. If we’re not working, a lot of people are not working.”