The notion that Indigenous people in Canada broadly oppose oil and gas projects is becoming an increasingly hard sell, as many First Nations communities are not only realizing the benefits of working with industry, but looking to stake their own claims on energy mega-projects.

It’s been a persistent narrative that opponents of Canada’s oil and gas industry eagerly wield even as a growing number of First Nations turn to energy projects to carve out brighter futures for their communities.

The Canadian Energy Centre has been honoured to share the voices of Indigenous people — leaders, business owners and workers alike — who see involvement in one of Canada’s key industries as a path toward “economic reconciliation,” offering more opportunities and better wages to help pull Indigenous communities out of poverty.

For Dale Swampy, a member of Alberta’s Samson Cree Nation who runs the National Coalition of Chiefs, any belief that there is broad opposition to energy projects by Indigenous people is far removed from reality.

“To say that we are all against development is ludicrous. We’re in favour of prosperity,” he says.

“People think we’re all on welfare and against every piece of development that comes our way. It’s frustrating.

“We know that the majority of chiefs are in favour of participating in major projects.”

Swampy’s viewpoint is more than just anecdotal – it’s backed up by the data.

CEC research analyzing the positions of some 250 First Nations in B.C. and Alberta likely to be impacted by oil and gas development found that a significant number were in either in support or offered no objection, compared to a mere handful that were opposed.

The data also showed First Nations involved in Canada’s oil sands industry has had a pronounced positive effect upon their employment and unemployment rates, employment income, and on their reliance on government transfers.

But while increased partnerships provide obvious mutual benefits, some First Nations leaders are leading the charge to control of their own destiny through ownership of major energy projects.

Perhaps most significant are competing bids by two First Nations coalitions looking to acquire a majority ownership stake in the $12.6 billion Trans Mountain pipeline expansion in BC and Alberta.

The Western Indigenous Pipeline Group (WIPG), which is offering ownership to the 66 bands through which the pipeline crosses, and Project Reconciliation, which represents 340 different Indigenous groups, are both seeking to buy into the project, now owned by the Government of Canada.

Shane Gottfriedson, Project Reconciliation’s British Columbia Regional Director, says ownership of the mega-project will help create prosperity for nations that have often struggled economically, and, by extension, socially.

“Poverty is normal for our people,” says the former B.C. regional chief and former chief of T’kemlups te Secwepemc First Nation.

“Other industries certainly have their role [in contributing to Indigenous prosperity] but TMX presents Nations the largest opportunity today.”

The still under construction pipeline project is already helping First Nations along its winding 1,150-kilometre route.

As of February, some 59 commercial agreements had been signed with Indigenous groups (45 in B.C. and 14 in Alberta) worth more than $500 million, which will assist communities in training, business opportunities and improved community services and infrastructure, depending on their needs. Those agreements have also led to more than $275 million in project procurement contracts for First Nations.

Electrician Jason Victor of the Cheam First Nation, some 50 kilometres northeast of Chilliwack, has managed to find work on the TMX project, supporting camp infrastructure. He has seen first hand how Indigenous communities can be transformed through partnering with the industry.

“Oil and gas is an absolute necessity when it comes to economic opportunity for Indigenous people,” he says.

“Energy is an opportunity for Indigenous unity, where we as Indigenous people are able to reconnect across B.C. in support of this unprecedented opportunity to raise our people out of poverty.”

Crystal Smith, Chief Councillor of the Haisla First Nation near Kitimat, BC has watched her own community evolve from an Indigenous enclave with little opportunity to one flourishing through its involvement in the LNG Canada export terminal project and the Coastal GasLink pipeline.

“Growing up today in our community has no boundaries — it’s absolutely amazing to see that if my girls want to be a carpenter or an electrician, there’s nobody saying you’re not going to get funded for school,” she says.

“If they want to do that, they’re going to be able to do it.”

Like TMX, Coastal GasLink has been a financial boon for First Nations communities, with an estimated $825 million in employment and contract opportunities paid out to date for Indigenous and local companies.

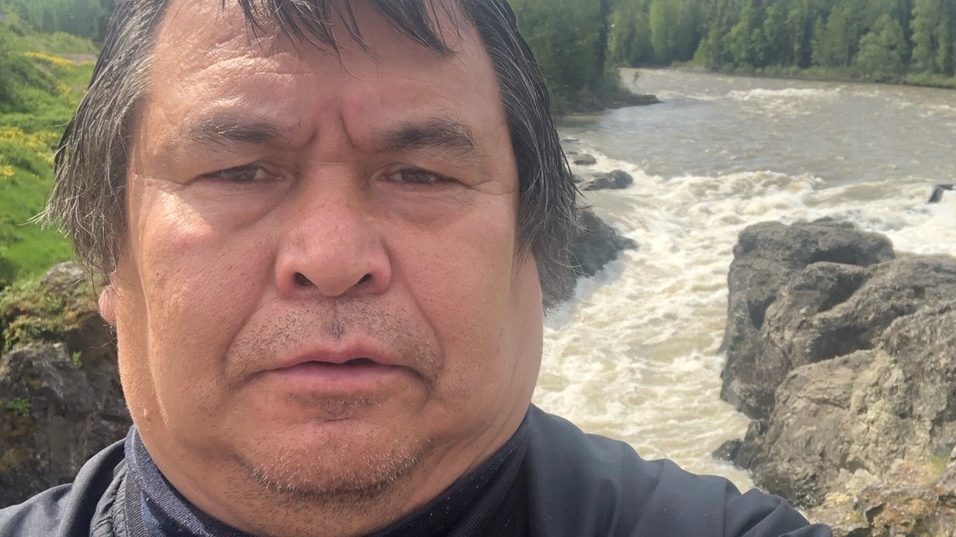

The project has allowed 52-year-old Phil Tait Jr. to find stable and lucrative employment after a life spent chasing opportunity in the often unpredictable natural resource sector.

“Both the forestry and fishing industries are dying in British Columbia, and Coastal GasLink presents the entire region with an opportunity for prosperity,” says the father of four.

“There’s a sense of pride in building one of the largest projects in the world right now.

“The way the economy is going, projects like Coastal GasLink can help save our communities, our government, and province.”