Building a port on Hudson’s Bay to ship natural resources harvested across Western Canada to the world has been a long-held dream of Canadian politicians, starting with Sir Wilfred Laurier.

Since 1931, a small deepwater port has operated at Churchill, Manitoba, primarily shipping grain but more recently expanding handling of critical minerals and fertilizers.

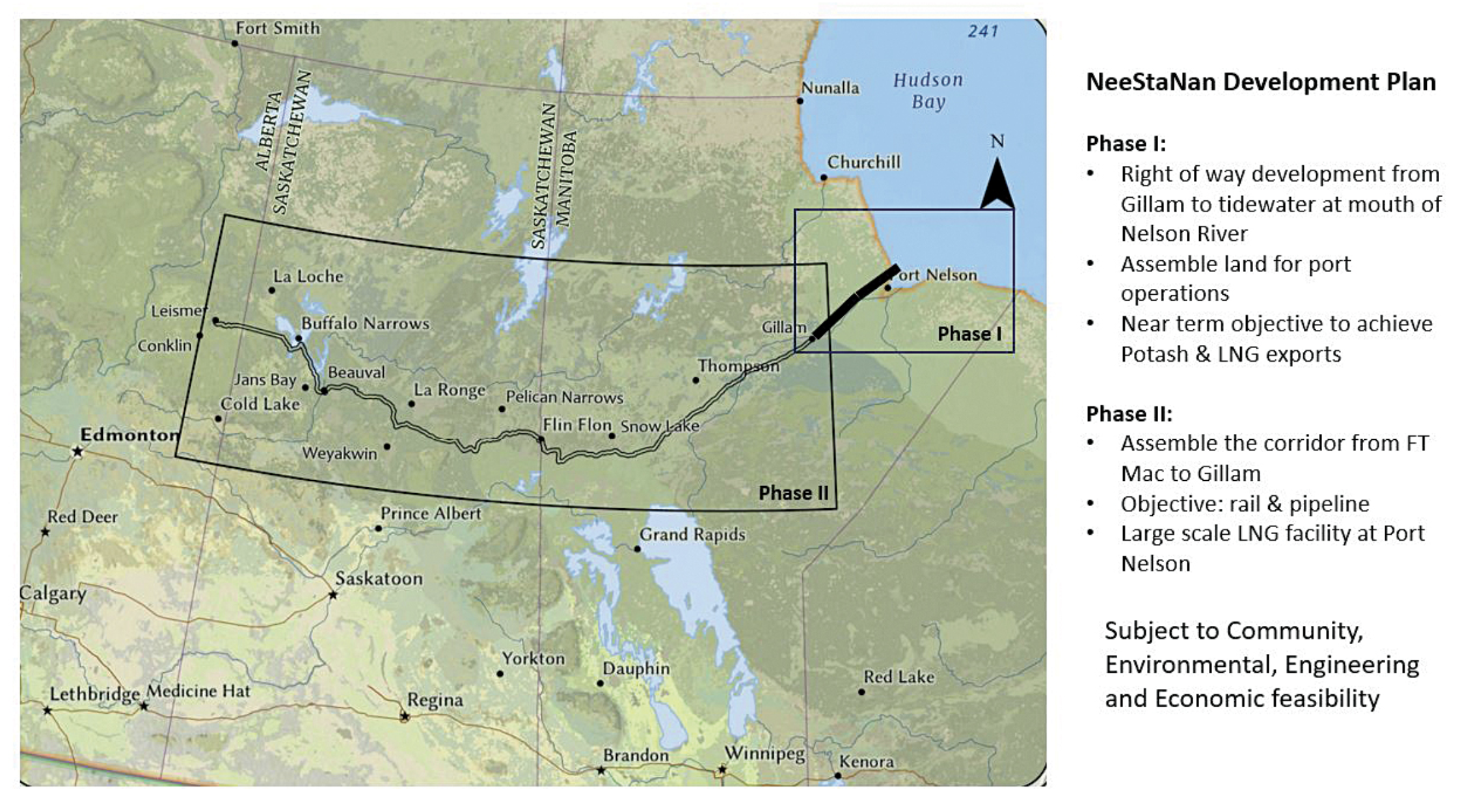

A group of 11 First Nations in Manitoba plans to build an additional industrial terminal nearby at Port Nelson to ship liquefied natural gas (LNG) to Europe and potash to Brazil.

Robyn Lore, a director with project backer NeeStaNan, which is Cree for “all of us,” said it makes more sense to ship Canadian LNG to Europe from an Arctic port than it does to send Canadian natural gas all the way to the U.S. Gulf Coast to be exported as LNG to the same place – which is happening today.

“There is absolutely a business case for sending our LNG directly to European markets rather than sending our natural gas down to the Gulf Coast and having them liquefy it and ship it over,” Lore said. “It’s in Canada’s interest to do this.”

Over 100 years ago, the Port Nelson location at the south end of Hudson’s Bay on the Nelson River was the first to be considered for a Canadian Arctic port.

In 1912, a Port Nelson project was selected to proceed rather than a port at Churchill, about 280 kilometres north.

The Port Nelson site was earmarked by federal government engineers as the most cost-effective location for a terminal to ship Canadian resources overseas.

Construction started but was marred by building challenges due to violent winter storms that beached supply ships and badly damaged the dredge used to deepen the waters around the port.

By 1918, the project was abandoned.

In the 1920s, Prime Minister William Lyon MacKenzie King chose Churchill as the new location for a port on Hudson’s Bay, where it was built and continues to operate today between late July and early November when it is not iced in.

Lore sees using modern technology at Port Nelson including dredging or extending a floating wharf to overcome the challenges that stopped the project from proceeding more than a century ago.

He said natural gas could travel to the terminal through a 1,000-kilometre spur line off TC Energy’s Canadian Mainline by using Manitoba Hydro’s existing right of way.

A second option proposes shipping natural gas through Pembina Pipeline’s Alliance system to Regina, where it could be liquefied and shipped by rail to Port Nelson.

The original rail bed to Port Nelson still exists, and about 150 kilometers of track would have to be laid to reach the proposed site, Lore said.

“Our vision is for a rail line that can handle 150-car trains with loads of 120 tonnes per car running at 80 kilometers per hour. That’s doable on the line from Amery to Port Nelson. It makes the economics work for shippers,” said Lore.

Port Nelson could be used around the year because saltwater ice is easier to break through using modern icebreakers than freshwater ice that impacts Churchill between November and May.

Lore, however, is quick to quell the notion NeeStaNan is competing against the existing port.

“We want our project to proceed on its merits and collaborate with other ports for greater efficiency,” he said.

“It makes sense for Manitoba, and it makes sense for Canada, even more than it did for Laurier more than 100 years ago.”

The unaltered reproduction of this content is free of charge with attribution to the Canadian Energy Centre.