As global oil demand rockets to record highs, new analysis shows that supply from Canada’s oil sands is on track to continue rising. And much of that growth could come with a lower emissions footprint.

For the first time in more than five years, analysts with S&P Global have increased their outlook for oil sands production, predicting it will reach 3.7 million barrels per day by 2030 – about half a million barrels per day higher than today.

The Alberta Energy Regulator sees oil sands production rising even higher, reaching 3.9 million barrels per day in 2030, according to its latest outlook.

But growth now in the world’s third-largest oil deposit is different than in the past. Oil sands producers aren’t building big multibillion-dollar new facilities anymore. They’re using their existing projects to produce more oil, and often that means reduced emissions per barrel because of improved efficiency.

S&P Global vice-president Kevin Birn calls it “an era of optimization.”

“They’re looking at ways to optimize the things they have, and in doing so squeezing the production higher, lowering unit cost and in the process often carbon intensity,” he says.

Era of optimization

For example, improving efficiency can allow operators to drill more wells without having to generate more steam for injection into the reservoir. This added production tends to come without significantly higher emissions.

“The absolute emissions associated with that production are roughly the same. They’re just getting more oil,” Birn says.

“That’s not always the case, but it’s generally the case because they’re leveraging their existing capacity.”

An oil sands increase of 500,000 barrels per day in less than 10 years may seem large, but not compared to the past pace of growth. In the decade between 2010 and 2020 production increased by 1.3 million barrels per day, according to the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers.

On pace for emissions reduction

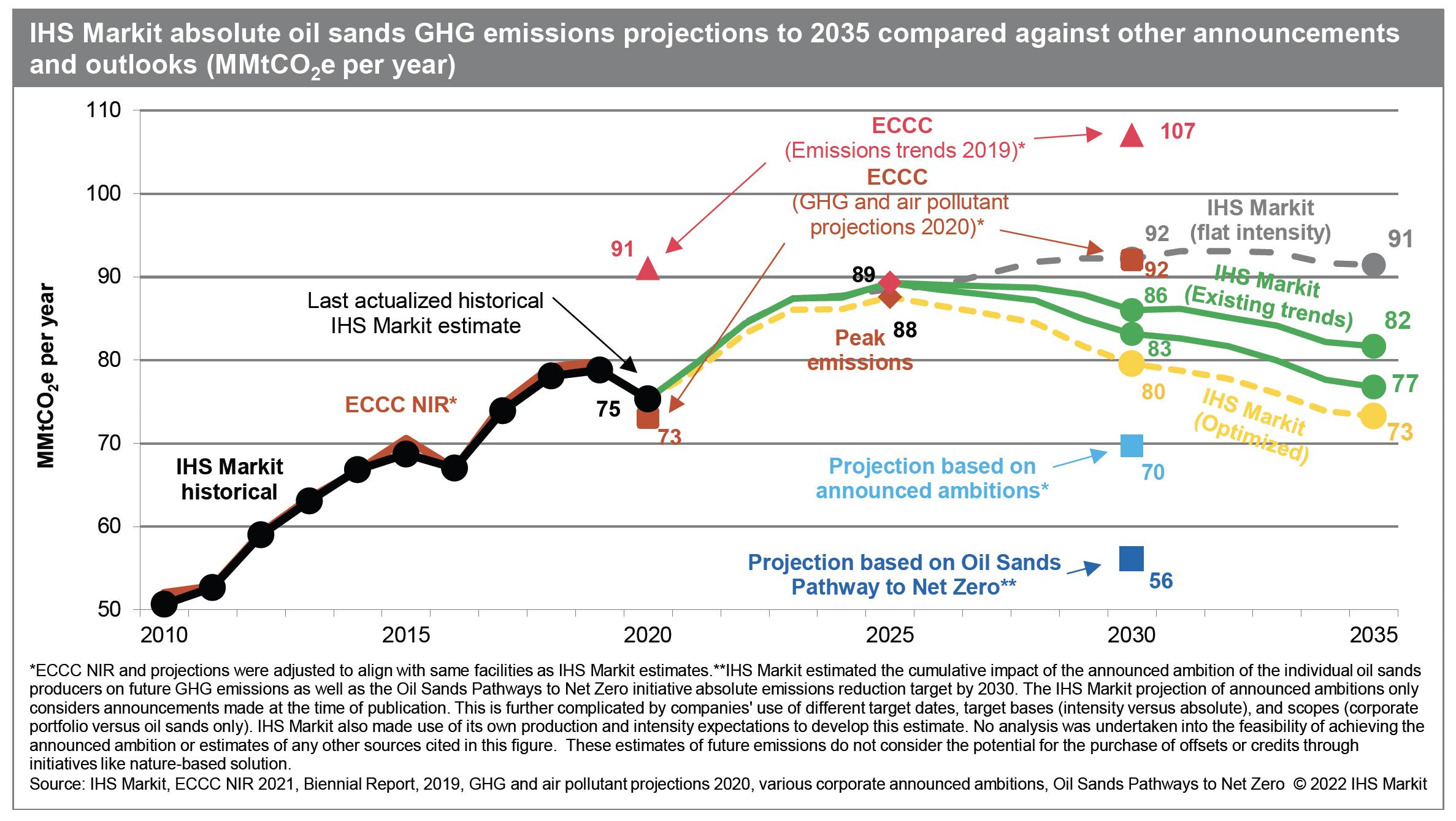

Slower growth means the success the industry has achieved in reducing emissions per barrel is likely to catch up and start bringing total emissions down as well, Birn says. A 2022 report by IHS Markit (now part of S&P Global) predicted peak oil sands emissions around 2025.

The downward trajectory is also seen by Kendall Dilling, president of the Pathways Alliance, a group of companies representing about 95 per cent of oil sands production.

According to Environment and Climate Change Canada, in 2021 total oil sands emissions were 85 megatonnes, a two per cent increase from 83 megatonnes in 2019, before the COVID pandemic roiled world oil markets. Since 2000, oil sands emissions per barrel have decreased by 29 per cent, according to Statistics Canada.

“A lot of the criticism of the GHG emissions from oil sands in the past was that they were on an absolute basis growing because we kept growing production. Our emissions per barrel have decreased about something on the order of 30 per cent over the last couple of decades, but that was always outpaced by growth of production,” Dilling says.

“Now with production having more or less flattened out, and us continuing to do all that good improvement and efficiency work, we’ve hit that inflection point where the trajectory is coming down. The kind of stuff we’re trying to do at Pathways is really about putting that on steroids and dropping it much, much quicker.”

The six companies in the Pathways Alliance have set a joint target to reduce total emissions from operations by 22 million tonnes by 2030, on the way to net zero emissions from operations by 2050. The anchor of the plan is building one of the world’s largest carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects.

Global oil demand

Global oil demand is set to hit a record 102 million barrels per day this year and reach 106 million barrels per day in 2028, according to the International Energy Agency’s latest short-term outlook.

The added oil sands production will help meet demand, Birn says.

“The reality is although we’re selling more and more electric vehicles — which will impact oil demand over the longer-term — the existing fleet remains dominated by the internal combustion engine, and will continue to support demand for these commodities,” he says, adding much of the demand growth is driven by China.

“This points to the fact more oil will be required, not only to meet demand growth that is expected, but also to offset production declines expected around the world.”

Running almost indefinitely

Longer term, the IEA projects that in 2050 global oil demand will still be above 100 million barrels per day. Even in the agency’s scenario where the world achieves net zero by 2050, oil and gas will still supply about 20 per cent of energy needs.

“Even the IEA’s most aggressive net zero scenarios still show significant oil and gas demand in 2050 because you can only transition so quickly,” Dilling says.

“There’s a tail end of that that never goes away because there’s non combustion end uses altogether for heavy oil like asphalt and petrochemical feedstock and carbon fibre. The planet is better off if that need is filled by decarbonized, highly responsibly produced Canadian oil.”

In the oil sands, he says, “you can basically run almost indefinitely because there’s so much resource that you have very little exploration risk. You know the oil is there. It almost becomes more of a manufacturing business at that point, and you just get better and better at it.”

The unaltered reproduction of this content is free of charge with attribution to Canadian Energy Centre Ltd.