For Jean-Francois Gauthier, space is the next frontier in the quest to reduce global emissions, and the view from 6,000-kilometres above Earth is that Canada is a leader in curbing the most polluting of greenhouse gases.

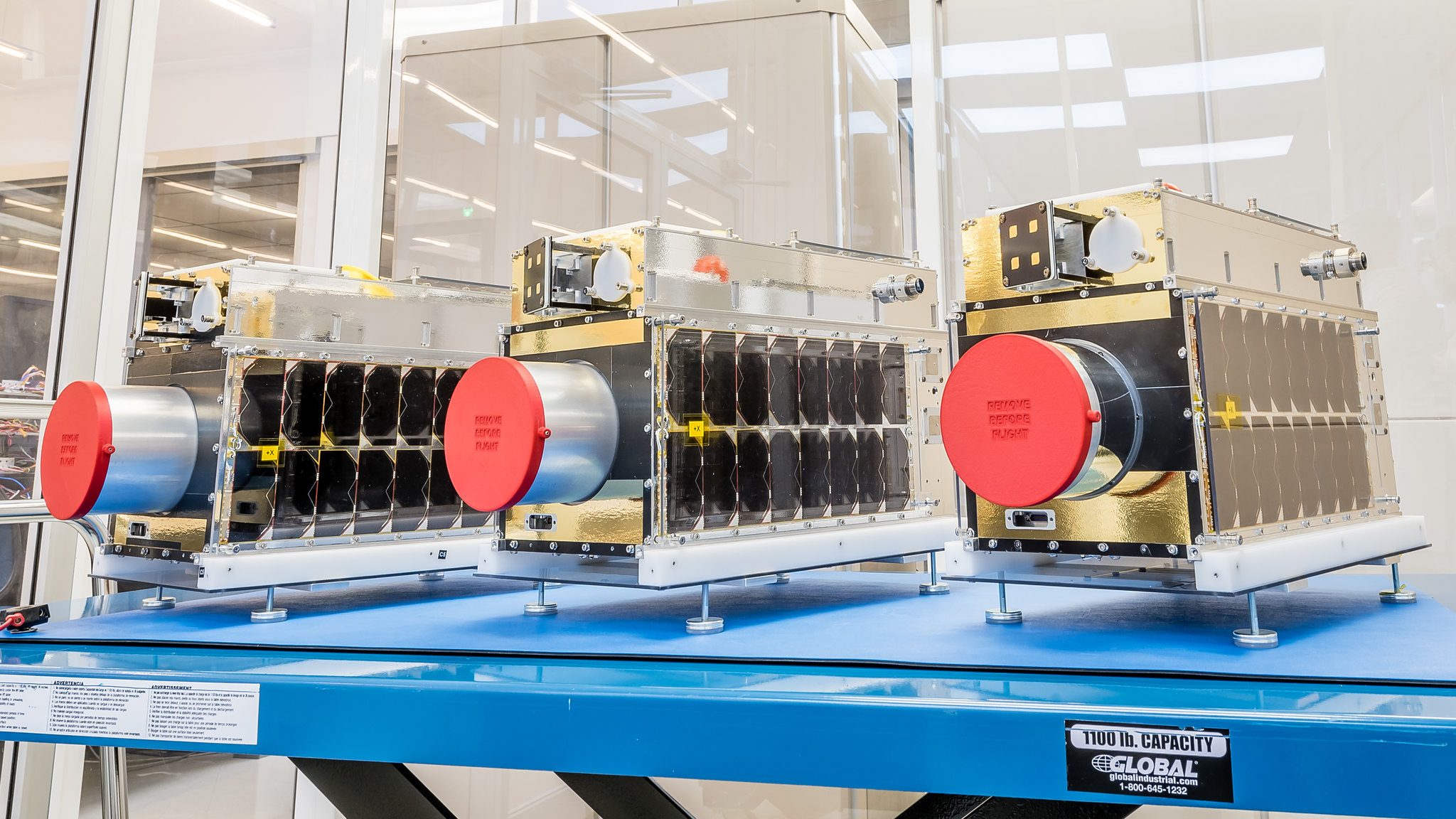

In April, Quebec-based GHGSat launched three more methane-sniffing satellites into Earth’s orbit – Mey-Lin, Gaspard and Océane – bringing its high-tech constellation of celestial emissions monitors to nine.

Gauthier, GHGSat’s vice-president of measurements and strategic initiatives, said after eight years of having eyes in the sky, one thing has become crystal clear – Canada is a world leader when it comes to taming methane emissions, a greenhouse gas many times more polluting than CO2.

“Canada’s performance from what we see anyway, with our satellites, is much better than the rest of the world,” he said.

“It’s shedding a light on the fact that Canada continues to be a leader on [methane emissions]. There’s always work to do – that said, if you don’t see as much with satellites, it’s encouraging because those are the biggest leaks that need addressing right away.”

TACKLING METHANE

Canada’s oil and gas industry has been working hard to tackle methane emissions over the last two decades.

Even as Canadian oil production grew 91 per cent between 2000 and 2018, Canada’s methane emissions declined by 16 per cent. Over the same period, worldwide methane emissions increased by 27 per cent while oil production only grew by 38 per cent.

In Alberta, the heart of Canada’s oil and gas sector, efforts to reduce methane emissions are well ahead of schedule, dropping by 44 per cent between 2014 and 2021, including a 10 per cent drop from 2020. That puts the sector within a stone’s throw of reaching (and likely surpassing) its target of reducing methane emissions by 45 per cent by 2025.

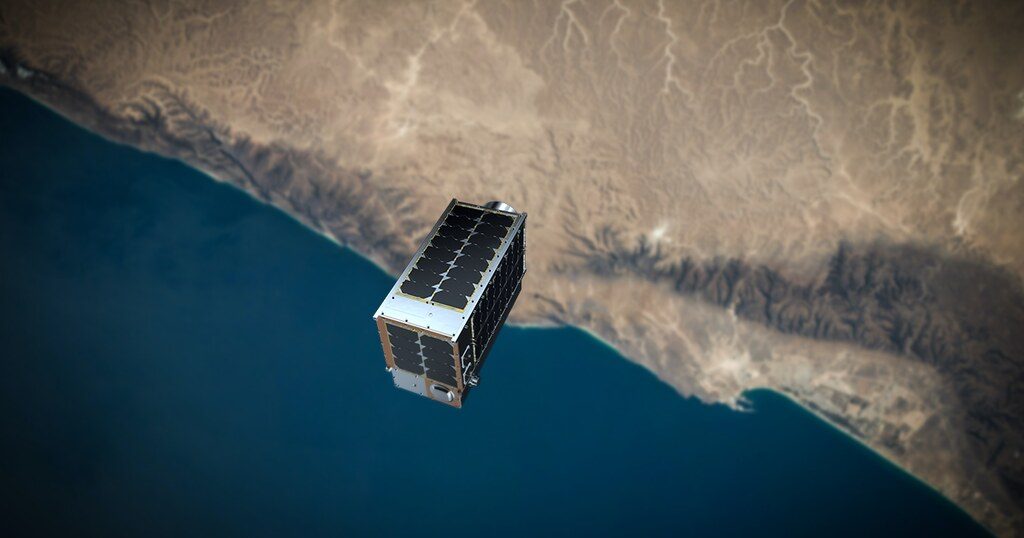

Gauthier said GHGSat is looking to launch three more satellites by year’s end and has sky-high ambitions to provide a true daily snapshot of global emissions. And it’s that data, viewable by industry, policy makers and the public, that can help determine the world’s heaviest emitters and act as a catalyst for action.

“Now we’re turning our attention already to the next batches because we have ambitions to get to 100 … ideally by the end of 2026, mid-2027,” he said, noting that would include a suite of satellites and airplanes to spot any major changes in emissions.

“The ambition really is to be able to look at all emitting sites worldwide on a daily basis. So now you can really decide where to take action and start eliminating some of those biggest sources.”

HUMBLE BEGINNING IN SPACE

Seen as a world leader in orbital emissions monitoring, GHGSat started in 2016 with a small, microwave-sized prototype satellite called Claire, in collaboration with Canada’s Oil Sands Innovation Alliance (COSIA) and other industrial partners.

She was joined in 2020 by her stellar sibling Iris, following a successful launch onboard an 11.7-metre tall Vega rocket from the Kourou International Spaceport in French Guiana. From there the company has launched a steady stream of increasingly refined satellites into orbit, each one bearing the name of one of the team members’ children.

The company contracts out its monitoring services to oil and gas companies, government and increasingly mining, waste management, agriculture and other emissions-intensive industries. While private sector data is owned by clients, GHGSat also offers searchable real-time emissions data available to the general public at a lower level of resolution.

Gauthier said GHGSat continues to work with the European Space Agency to provide ongoing climate data, and is in talks with NASA, which is currently assessing the company’s platform to be part of its commercial small satellite data acquisition program.

Last year, GHGSat’s six operational satellites observed over 500,000 sites in 69 countries, measuring some 179 megatonnes of CO2 equivalent methane emissions, which equates to the same annual emissions of 38.6 million cars.

Gauthier said GHGSat targeted methane not only due to its heavier environmental footprint, but due to the fact that its easier to measure from space.

CO2: THE NEXT FRONTIER

However, he adds with improvements in technology the one of the next trio of satellites set for launch will key in on CO2 in an effort to provide a more complete picture of the planet’s greenhouse gas hotspots.

“We’re confident that using the same techniques that we’ve been using for methane we can use for CO2, and then be able to zero in directly to the sources,” Gauthier said.

“Industrial sites like cement plants, power plants, steel mills, aluminum smelters – these kinds of large CO2 emitters, we should be able to measure quite readily.”

Gauthier said getting a true picture of the problem is the first step. The next step is to find solutions to heavy emitters.

Coal use is expected to reach record levels this year as the global energy crisis continues. Liquefied natural gas from Canada can make an immediate difference in reducing emissions, with a report from Wood Mackenzie showing that if Canada increased its LNG export capacity to Asia, net emissions could decline by 188 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent per year – about the annual impact of taking 41 million cars off the road.

Canada is also a world leader in developing carbon capture and storage technology, accounting for 15 per cent of global capacity despite producing less than 2 per cent of global emissions.

“The bottom line is that technologies are here, not just to measure, but to fix leaks and take care of these greenhouse gas emissions,”

“It’s really time to take action. That is, I think, is probably the most exciting thing is that the tools are there, and now it’s time to use them.”

The unaltered reproduction of this content is free of charge with attribution to Canadian Energy Centre Ltd.